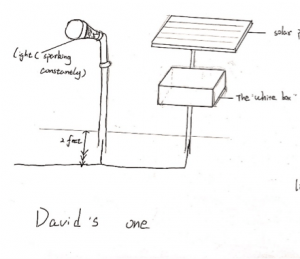

Lion Entry Deterrent Systems (LEDs), colloquially called "Lion Lights", utilize flashing solar-powered LED lights.

These flashing lights imitate human presence by mimicking herders using torches at night to safeguard their livestock, creating a visual disturbance that discourages lions and other predators from entering the Massai bomas (cattle, goat and sheep enclosures), thereby enhancing safety for animals and humans especially in regions prone to lion encounters.

Despite their efforts to preserve their traditional Maasai culture, increasing urbanization and the designation of areas once used for grazing to national parks and reserves have significantly restricted their ability to freely herd cattle across expansive lands. As a result, the Maasai have increasingly shifted from their traditional nomadic pastoralism to a more sedentary lifestyle.

The reality how Massai live today is quite different from the past. They have evolved, and many aspects of their lifestyle, including lion hunting, have changed. Due to conservation efforts and changing attitudes, the traditional lion killing has become rare. The Maasai are now more involved in wildlife conservation projects, recognizing the importance of lions in the ecosystem and the tourist industry, which benefits their community.

The pastoralists living around Kenyas National parks are willing to tolerate this uneasy coexistence by leaving the remaining corridors open and giving up economic activities that are not in line with wildlife conservation, such as crop farming or keeping large herds of livestock, if both government and wildlife conservation organisations ramp up compensation processes for their losses while compensating them financially for protecting biodiversity.

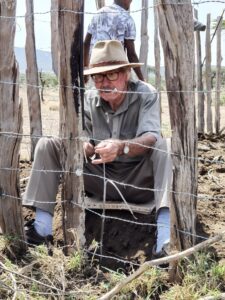

David Mascall's "Lion Lights" help to secure the bomas (Homesteads) around the park borders. One boma at a time.

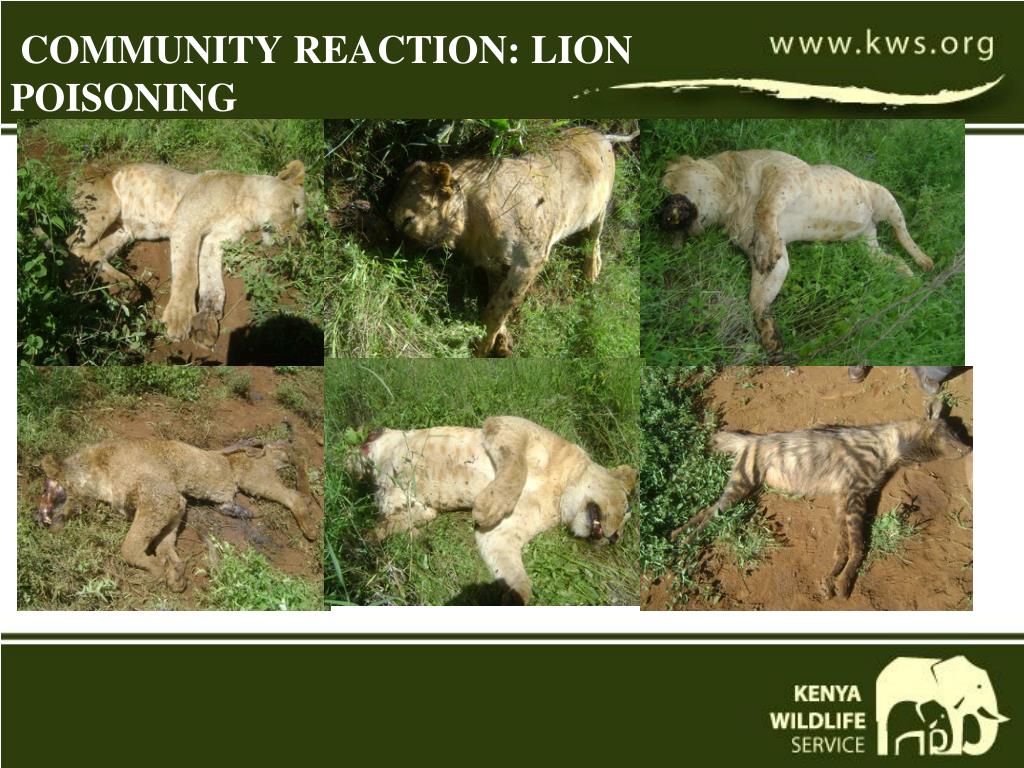

Retaliatory killing in its worst form is conducted using poison which can kill entire prides and a host of other species—from elephants to vultures to wild dogs, leopards and cheetah.

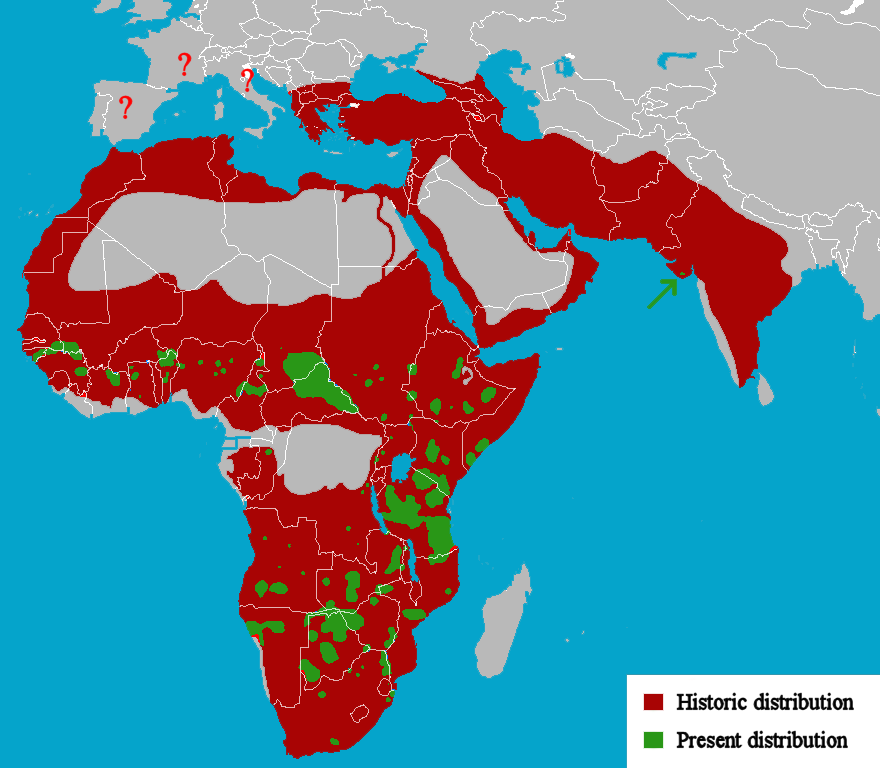

With rapidly growing human populations, there are increasing influxes of livestock and herders in search of better grazing within wildlife areas across Africa – resulting in more conflict between people and lions. Livestock also compete with wildlife for resources, causing declines in the wild prey lions depend on. In many cases influxes of herders are also associated with secondary problems such as elevated poaching. Many such movements of people into lion landscapes result in complete habitat loss due to conversion to agriculture and settlement.

There is also a threat in certain parts of Africa from the targeted poaching of lions for their body parts, such as skins, claws, teeth and bones.

Human settlement and development are gradually creating ever smaller and more isolated pockets of wilderness in which lions and their prey exist, making it challenging or impossible for lions to roam or disperse safely and restricting gene flow which leaves populations vulnerable to disease and other threats.

The Maasai are becoming farmers. One cause of shrinking predator habitats is human population growth. Over the past 50 years, Kenya’s population has tripled, bringing significant changes. In the Kenyan ecosystem, many Massai are shifting from traditional pastoralism to farming around the protected areas. Land is concerted into crops while still maintaining strong cultural and economic ties to cattle herding. This expansion of farming reduces natural habitats, leads to more elephant crop raiding, and decreases pasture land. As a result, many Massai now take their cattle into the national parks and reserves for grazing. Supporting livestock farmers with Light for Life's predator entry deterrent systems is a small, but important piece in the puzzle of predator conservation in Kenya.

© 2025 Light-For-Life. All rights reserved | Designed and Developed by Tomorrow Labs